Anyone who has traveled and spent more than a few days in a foreign culture can confirm that one of the things that does not translate easily is humor. Our experiences as expats in Mexico only confirm this suspicion, although I think there are positive lessons to be learned from other cultures when it comes to humor.

Comedy NOB has become–as so much else–heavily politicized. You can laugh at the outrageous behavior on one side, but there are *crickets* on the other side. Meanwhile, a growing list of things once considered humorous are now off-limits: officially (and sometimes criminally) liable, offensive, and unforgivable.

Not so much in Mexico. Mexican humor is generally much sharper, politically incorrect, and fatalistic. There are a few topics which are off-limits to Mexican humor: national symbols (the flag, the anthem), some historical figures (La Guadalupana, Los Niños Heroes), and always, always, ¡SIEMPRE! anybody’s mother. There us nothing in Mexico equivalent to “the dozens” up north. Most everything else is available for ridicule.

Start with nickknames, or apodos. I am not talking about those which come with your given name, like men named Jesús being called Chuy, but rather the ones given you by your friends or family, and often due to a physical characteristic. So you might call your friend gordo because he is/was fat (or maybe very thin), chapo (shorty), tartajas (stutterer). Yes, the characteristics can be somewhat crude by NOB standards, but are not meant or taken that way in Mexico. Knowing someone’s nickname and using it is a sign of inclusion and affection, even though the names might not always sound that nice.

Joking about sex is becoming more common, if only among the younger and less cultured. However many Mexicans enjoy the double-entendre, or albures. These word-plays can be subtle or blatant, and may involve food. Be careful if you are ever asked how you like your eggs (huevos) or chiles. If your answer elicits smiles, you might be the accidental victim of an albur.

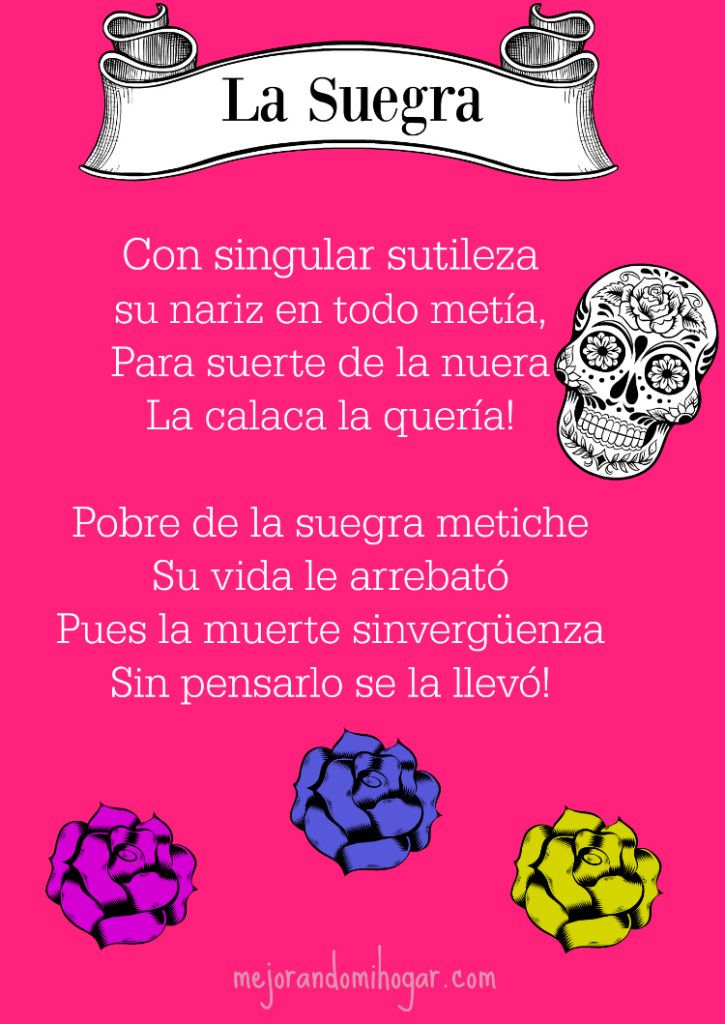

Death or tragedy is definitely on-sides for humor. Our Spanish teacher told us about a young Mexican entrepreneur who launched a video game about saving those trapped Chilean miners…while they were still trapped! As he explained, it wasn’t because they were Chilean…he would have done the same if they were Mexican! If you follow this reddit link, you’ll see a video of a float in a Mexican parade. The float is for the local search and rescue team, who stand (on the float) in a simulated demolished building. Watch closely, and you’ll see a bloody arm waving from under the rubble! This is, after all, the culture that brought the world calaveras, (literally skulls), short poems predicting the amusing, ironic, or poetically just way someone (at times rich or famous) will die.

And of course, there is the famous story of the Mexican fans chanting “ehhhh, puto” at the World Cup. This vulgar chant (I wont give you a translation, just take my word for it) is very common in the Liga México, but FIFA threatened and then fined Mexico because its fans would not stop chanting it during every goal-kick. Despite pleas from the team and the government, the chant only grew louder, and continued. Eventually, FIFA gave up.

Most Mexicans insist that while the word has several–all vulgar–meanings, the chant is in jest, and therefore permitted. Look at any YouTube video, and you’ll see this in play, which illustrates the Mexican view: it’s not what you say, it’s how you say it. Said with a smile, even a slur becomes nothing more than joke between friends.

This is a universal principle. Even in English, we understand the difference tone, non-verbal cues, and context make. If a man greets a woman-friend with a simple “That’s a nice dress!” it would probably be taken as just a compliment. Change the response to “That’s a NICE dress!” with an eye-roll on NICE and you have a coded insult. Change it to “That’s a nice dreeeeeesssss!” with a leer on the last word and you have a harassment case. “That’s a nice dress?” with a verbal uptick on the end and you have an implied difference of opinion on the very concept. The words remain the same, the message varies greatly.

Mexico applies this same concept to humor. NOB, certain terms have become so politically incorrect that they are forever banned. Perhaps this reduces the frequency and hurt of offensive statements, perhaps not. It certainly makes people more wary. I will bet somebody reading the last paragraph thought “why should a man even be commenting on a woman’s dress?” Point made!

The need for humor to grease human interactions is eternal; words come and go. “Gay” was a slur before it became the title of Pride Marches. Irishmen calling each other “shanty” or “lace-curtain” was the beginning of many a fatal brawl, once upon a time. And don’t even begin to delve into the never-ending debate on the rules concerning use of the “N-word” within, and outside, the African-American community. Even the word “gringo” which simply derives from the concept of someone you can’t understand, falls into this category.

Words can hurt, no doubt. Yet they have only as much power as we give them. And no one wants to live in a humorless world. Just remember, “smile when you say that!”

Great Float: six and a quarter guys…and s rescue dog who is ignoring the arm. One question: what does “politically” incorrect mean? Been puzzling over this one.

“Political correctness” as a concept grew out of some older cultural accommodations. I know you remember when women were referred to as Miss or Mrs, indicating martial status. The use of Ms (mizz) grew as a cultural accommodation indicating a rejection of the cultural norm, but it was just that, a cultural norm. Sometime more recently, the use of pronouns, gender, and even homophones have gone from cultural norms to political (as in policy, or law) norms. Incorrect usage is considered by some as transgression, displaying a lack of respect or an ignorance of etiquette (in the US) and fines and civil penalties (in Canada). Hence “political correctness.”

Great post. Love your blog, Pat.